Les Sharp, Photographer.

Some Biographical Notes

My fascination with photography started in the 1960s with the publication of two iconic images; a baboon in full flight turning to confront the chasing leopard on the open plains of Botswana, and in Yellowstone Park, a husband shoving a grizzly bear into a sitting position, on the driver’s seat next

to his horrified wife. Today, the images still act as a carrot on a stick, taunting me to achieve their standard with the taking of the next photograph.

My scientific career began in 1965, graduating from Sydney University with a PhD in the field of Fusion Physics. This discipline reproduces the process of the sun and promises to provide vast quantities of electrical power for mankind with a small physical footprint, no greenhouse emission, and using isotopic hydrogen as fuel sourced from the sea.

Then there was a three-year postdoctoral stint at Cornell University in the USA, followed by ten years of research at the UK Atomic Energy Culham laboratories near Oxford. It was a marvellous time with Culham being the centre of the world for fusion research, and where, at morning and afternoon tea, one could sit next to world leaders and Nobel prize winners and discuss projects and problems without formality or appointment. At Culham, the scientific staff were intensely interested in illustrated travel reports from far off places, the more remote, the better. Probably this interest was a hangover from the heroic period of the British Empire, over which, it is said, the sun never set.

Then in 1977, the Australian National University proposed an offer I could not refuse. A tenured research position at Associate Professor level with six weeks annual leave, one year study leave every seven years, and a large budget.

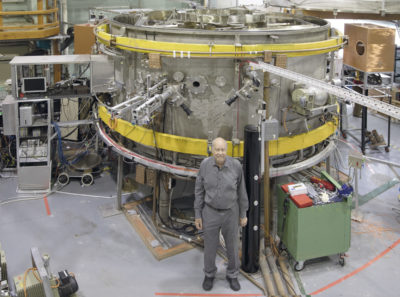

The opportunities seemed endless; to design and construct H1 a magnetic confinement experiment to study how the plasma was escaping faster than expected, to travel from pole to pole and photograph exotic places, and, to be the photographer for the Australian and Russian Gymnastic Federations at seven World Championships leading to an Order of Australian Medal for contribution to the sport of Gymnastics.In 1997 the H1 team won the physics prize in Prime Minister Paul Keating’s Science competition, receiving $7,000,000 to upgrade H1 to a national facility. The prize, however, was potentially a poisoned chalice as the objective of the ANU to publish scientific papers, conflicted with the strict deadlines required for accepting tax payer’s money. So, in the following year, I retired from the ANU to concentrate on photography. Finally in 2017, after being operational for 25 years, and with its senior staff retiring, the H1 experiment was being transferred to China to be part of that country’s contribution to the world fusion research program.

Looking back over my career I detect an ironic twist between the physics and the photography. As a student, I worked on SILLIAC, the first mainframe computer in Australia (it had less computing power than some present day toys) and rejected the newly discovered Light Emitting Diodes as the subject for my PhD thesis. Within one lifetime, the development of computing systems and state of the art LEDs would blend into the ubiquitous smartphone, with its simple to use camera and instant wifi data transmission. Placed in the hands of millions of casual photographers, these smartphones have become the major challenge for traditional photography in a number of genres leading me away from a reportage style into one of more abstraction.

Ah yes, Times, they are a-changin’.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.